Dynamic Permanence

The boy loved comics.

Not the Batman, kapow, superhero comics, but the funny pages; the comics that made you laugh or made you think rather than excited or suspended you.

The boy loved to laugh and to imagine and to invent, and the methodically continuous lives of the comic-book characters gave the boy both hope and stability.

He favored one publication above all others. One that no longer appeared in the newspapers and that the boy had only discovered by some immemorable coincidence. The only thing that mattered to him was that he loved it. He never considered why he loved it. Such questions had no use to him yet.

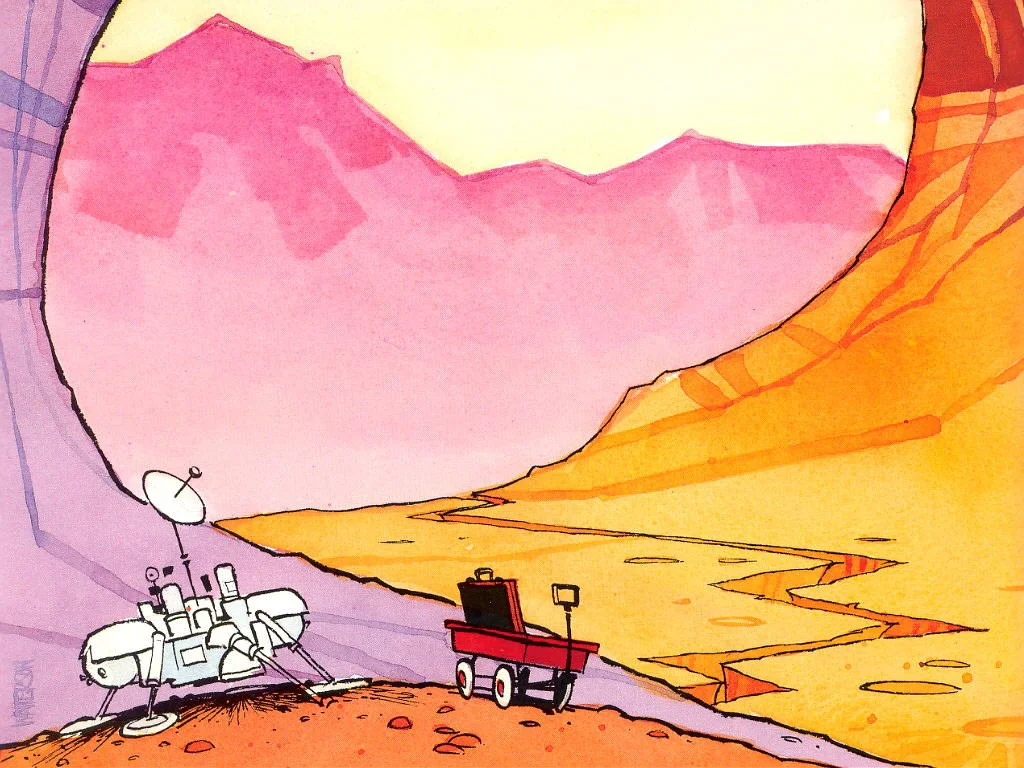

To him, Calvin and Hobbes were not characters, but friends. Their banter, antics, and philosophical rantings affected the boy deeply, creating in him such emotions that one could often find him bent over a collection with tears streaming down his eyes, falling onto the 12-dollar volume that he valued so highly.

Because these comics could only be read in volumes, the hours, and sometimes days that progressed after a volume’s purchase were spent in complete rapture. They put a powerful spell over the boy as he consumed them whole, hungrily devouring his relationship with these drawings as an addict would his chosen poison. There was never any ill intention in the boy’s ways, he simply wanted companions who thought about the world the way he did. He thought about life and death, the universe (whatever subject) with gravity, despite his profound misinterpretation of these subjects. Other children his age seemed to lack this certain precocious quality, and although children were as amiable as he expected them to be, he found his first true mates in static boxes. Perhaps that was partly why he loved them; they could never change and they could never hurt him. And the fact that man created them, beings that lived more on paper than many live on earth, gave the boy a love of humor and irony. He learned to mix pleasure with sadness, to accept the world’s volatile potion with a smile. He learned to drink to health even while sick. He thought he knew how things were.

When he received a new volume, the boy would recede into his room with it until it had been completely and thoroughly engulfed. Laying on his bed, focusing upon his meal, he would fidget restlessly, changing positions so that sometimes he held the book above his head while he rested on a pillow, and at others he peered at it from the side or from above. He read so long that his arms grew weary and his neck ached. Sometimes his eyes would begin to blur and he would have to blink and rub them when they would not cooperate with his commands. He was impatient with his body, and often found physicality cumbersome and frustrating. When the volume’s floppy pages would escape his fingers, fall inwards, and momentarily block his view of the current strip, he would get angry, treating this fractional lapse as meaningful and purposeful aggression.

He thought he understood the world, and in the context of the comic, he did. But the world, unlike a comic strip, has no eternal logic. There was a great scale in his head which held on its illustrious platforms both his intellect and his emotion. In the balanced person, such a scale would favor a side, therefore definitively determining that person’s traits. The boy, however, experienced a fluctuation: an inability to stabilize what, by definition, does the stabilizing. For him the internal temperate scale was not grounded on a secure platform, beholden to a world in which things can be measured definitively, one time. His ideas and impressions had been “wrong” before so he never felt entirely certain that the way he felt was right to feel. He was afraid and the comic helped him figure out who he was.

He dreamed about Calvin and Hobbes, and even spoke to them when he was alone. They became more than characters to him, they began to have an (albeit limited) existence. The difference between physical and fictional being became harder to define, and the scale seemed to fold in on itself, to become a point instead of a line.

He began to experience his life in fragmented, dramatic sequences. Sometimes he would pose and gesticulate jerkily, speaking in short, pithy phrases as if his life were being captured in frames. Sometimes, his parents found, he would even close his eyes for a few seconds after uttering such a phrase, crystallizing and solidifying it so that it would never end. They didn’t understand it so they thought it was cute.

When he thought no one was looking he would often allow himself to see Calvin and Hobbes, to go on hikes in the woods with them and to combat those sarcastic monsters under the bed. Sometimes the scale in his head would collapse so thoroughly that he could not tell the difference between what was real and what he wished was real. So, it seemed, he had no concept of reality.

He liked still lakes, ancient mountains, books, and VHS cassettes. He liked pictures but he couldn’t quite understand why everything that he liked had the tendency to make him cry or to look around for someone else. He almost never slept, but sat up imagining the way his future house would be laid out, how many animals he would have, and where he would go exploring. But in all of these scenarios the dreamer himself never changed. He simply couldn’t, or refused, to imagine what it would mean for him to be different.

He had never truly experienced finality, and the thought that every single moment of his life would not be viewed, recorded, and evaluated individually had never even crossed his mind. He assumed that things had meaning, that purpose was at work in every existence, every action. He did not yet know what it meant to be lonely, what it meant for things to end.

He wanted to stay the same forever like a lake or a mountain or a VHS and he sort of assumed that he would. Why wouldn’t he? According to his observations his parents had never changed and his best friends, his characters, certainly hadn’t. If only someone had given him Keats to read, he might have identified his obsession with damming and compartmentalizing the constant flow of time. He wanted his life in sections that could be analyzed, picked up, carried around, and revisited. He didn’t think in terms of straight lines, but in points or spheres.

One day he sat reading, “The Indispensable Calvin and Hobbes,” the last of the comic that remained unread to him, blissfully unaware that he was about to read the very last un-experienced strip in existence. Unconsciously he began to read more slowly as he approached the anthology’s final pages, flipping them almost reluctantly. He stopped before the last page and found himself unable to continue forward, his limbs simply would not move and he was frozen.

He passed out in confusion, head drooped over the page, mouth drooling, eyes still moving back and forth in silent protest. That night he dreamed of rivers and falling trees, of moving cars and clouds floating by made complex by the wind, of boards of wood and levels, of iron. He awoke sweating, unsure of how he became there. He never called for his parents when he was awake at night but this was different. He felt afraid for reasons beyond his comprehension and called out into the dark.

He forced his keepers to take him to bookstore after bookstore, searching feverishly through the comic sections for any iteration of the strip that he had not yet ingested and internalized. Rifling through shelves and leaving them disheveled vestiges of order. The order that had informed his life up until now was proving to be false and temporary. What good is order if it does not last? It was the first time he asked questions to which the answers were: “That’s just the way it is.”.

For a week or so he avoided reading his favorite books and was uncharacteristically moody, preferring to stare, half-lidded at television advertisements than to think. He never wanted to think again and he realized that he had never once received what he wanted. Did anyone?

After that week passed in a timeless blur, he was emboldened (or desperate) enough to reach for the anthology and flip to the last page. He read it, tears blurring his clear eyes and reddening them. He finished it and for the first time understood death. He had seen things that were dead and things that were alive, but somehow never managed to connect the two. By finishing the anthology he had killed his best friends and felt responsible for their demise. He felt a murderers’ guilt; his sadness, he felt, should have been powerful enough to resurrect them. He regretted. He felt like Eve. He felt doomed. He never wanted to feel again.

He had visions of angles, divisions, tree limbs breaking, and glass shattering. He broke out of the individual boxes in which he had been living his life and poured morosely forth, frothy with sudden explosive movement. He thought of God.

The stability of fiction rubbed against and inflamed the instability of reality, creating uncomfortable friction. He was chaffed raw and felt newborn, confused and utterly fresh. Not only could things not be revisited, but they couldn’t be changed either. Once something happened, it happened one way only, despite the differences in perspective. He became scarily, almost sociopathically objective and yet he cared so deeply that hurting another living thing was never even a thought. He just wished that things were different and lacked the power to change them.

He resisted reading for a time, the character’s passing from text to thought was too painful for him to bare. His first forays back into literature after this traumatic realization were serial, in which characters (or at least universes) were somewhat consistent between publications. He no longer trusted the world, but he gradually learned to view it without suspicion. After all, it is in ones’ self that trust is most vital.

Much later, when he began living for instead of from himself, he learned that the division he so staunchly created between reality and fiction need not actually exist. He learned to turn his own life into a story and to eschew his own criticism. What he discovered then, was creation and reveled in it like only a child can. He learned that things can change and stay the same at the same time, that reality and fiction cannot necessarily be separated. That even objectivity may not exist and that existence doesn’t have to either. The world is what it is, and what you make it too.