The Study

There was a study.

A small American town was observed. Its people scrutinized, its traditions evaluated, and its children tested. Scientists in white lab-coats, government officials in stiff suits, and decorated military personal watched them from the shadows--the nooks and crannies--their Presence exerting a subtle and intangible power over the townspeople. They felt mammalian quaverings, like a deer’s impulse to flee moments before an earthquake. Men imagined footsteps behind them and women clutched tightly at their children, to whom the fear of observation was foreign.

The serene night, yet unpolluted by light and sound, began to assume a less charming atmosphere, adorning instead a sinister cloak which shrouded these average Americans in suspicion. Eyes were lowered and foreheads were tipped in slimy innocuous enmity; the town, once so communal, began to split, fractally, regressively down to the isolation of each individual from each other. First in two (like cells) and then exponentially; illusive divisions arose between ideology, occupation, economic standing, race, age, interest, family, gender, name, and then finally the very skin they occupied.

They began carrying weapons, building bunkers, reinforcing home security systems. Businesses retained the right to refuse their service to any one. Shadows appeared where no object existed to cast them. The very ground seemed less accepting of feet--the rate of tripping, slipping, and falling increased by a quarterly rate of 17%, by the observers’ estimation. Bars, coffee-houses, and movie theaters went out of business and the police force received a record number of applicants. The parks were deserted, apocalyptic.

Nestled between two great mountains in a fertile valley blessed and intersected by a lazy, meandering river, the town had always felt protected and provided for, nourished and caressed. Isolated even by time itself, almost nothing, architecturally speaking, had changed since the early ’20’s. Home and garden magazines might describe it using the word, “quaint”. Generally, children played baseball and adults worked the land, town-meetings were full and men drank with the authorities after hours, crowding the local public houses. But Presence had tinged the place. What was once charming was now outdated, obsolete, decrepit. The town began to resent itself, its very township.

Each person, in adherence to the study’s parameters, was at some point given a chemical, an experimental drug that was, theoretically, designed to stave off death (whatever the cause) for an unknown period of time. Should the body lack sufficient blood to fully circulate oxygen within it, should entire organs be damaged or missing, should the body be mangled beyond personal recognition, the drug, the miracle pill would animate that body still. The chemical assumed all necessary bodily functions, performing the duties normally executed by the corporeal employees mentioned above, through other means, even supplanting electrical stimulation as the dominant form of synaptic and muscular communication. Every man, woman, and child in the town was given this chemical at some point during the observation period. Some were injected while sleeping, some left their drinks alone just a second too long, some ordered pizza delivered from a corporate chain, and others simply entered buildings with central air. The entire population having been inoculated, the observers simply waited, doing everything by the book I might add, until someone died.

Before the study, the likelihood that a townsperson would die was impossible to conceive. But now... they felt death around every corner, taking precautions that actually hindered their safety. Accusations took the place of praise, growls that of laughter. New words like “Spite” and “Grudge” took shape in their minds and were conceived through action. Crops were sabotaged, flocks led astray, and establishments (with character) were burnt and replaced. Something was about to happen, a force of nature, no spark or push necessary. Only time.

And then, like they knew it would, it happened:

Every year (the one tradition that remained) there was a parade commemorating the town’s prairie origins. Floats were constructed depicting men and women in thick cotton garments squinting forwardly against the sun, a small and well known play about town legend, Jericho Jim, was performed to its exact historical specifications, and the Mayor regaled his constituents with an origin story. Banners festooned Main St., American flags waived, and the sky was suspiciously blue and clear. Forebodingly so.

Out of that clear blue sky, an unforetold electric bolt struck the boy playing Jericho Jim during his monologue, right there in front of everybody, on the top of his wary, anticipatory head, killing him instantly. The townspeople watched in silent immobile horror as bespectacled scientists, grinning officials, and grim warriors rushed from alleyways, manhole covers, and rooftops, surrounding the dead boy. Being technically dead, his body was now government property and his family had no right to it. As measurements were being taken and observations recorded, the lead scientist, a hairless, insidiously hygienic figure, produced a bullhorn and began explaining to the townspeople what in the world was going on. His accent, they couldn’t help but feel, sounded vaguely Bavarian, animatedly-pitched, and trustworthy.

“One of you, a boy no less, has been killed.” The scientist’s blue eyes, filtered through trifocals, were clear and shining and empathetic. “A tragedy! A waste of such precious life and time! Struck down in youth by Chance!” He turned his head slowly, looking at them all individually, eyes widening and narrowing with apparent grief. The people felt his sorrow and began to weep, praying for the boy’s safe passage. “Death, which you have all felt, has finally arrived. But! Despair not! For there is a solution! We, your protectors, have taken a liberty. We have given him, this poor, unfortunate boy, a chemical that will, as you are about to see, push death from him a little longer.”

There was a stirring silence until a man, judging by the gruff voice, yelled out, “It’s goin’ bring ‘im back ter life? What, like Jesus did Lazarus?” The lead scientist chuckled amiably. “Well, no, my good simple friend, not exactly. You see, the boy will not be “alive” like you and me,” he used air quotes, “meaning that blood will no longer flow through his arteries and electrical signals will no longer travel along his nerves.” He assumed the roll of teacher, folding his hands philosophically, exuding patience and good will. “As you can see here, here for your selves, his head has been severely damaged, melted, leaving his sense receptors, those being the eyes, ears, nose and mouth,” he produced a pointer and indicated their facial locations (or lack thereof) on the boy’s head, “unusable. The wonderful thing about Extenze (which apparently was the chemical’s pharmaceutical name) my good friends, is that it does not require a functional body to operate effectively within. If we found a way for it to chemically interact with a stone, it would endow it with sentience and motion. So, despite this poor, poor boy’s lack of physical life, Extenze will allow him to function normally.” At this he smiled and spread his arms wide, messiahcally, inviting them to love him as movement could be heard behind his back.

The crowd cheered as the boy’s body righted itself in the proper bipedal, homo-sapien fashion and turned, eyelessly, to face them. The town, along with its observers, watched as the boy’s hands felt his melted head frantically. His voice projected from thin air (for his mouth was fused shut) questioning what the fuck was happening. Military men ran to subdue him, binding him in high-pitched plastic, scientists rushed him into an armored vehicle (which had been camouflaged as an ice-cream truck) and government officials created an impenetrably smiling barrier around the lead scientist who, pedagogically, continued:

“It is up to you, my good, simple townsfolk, to keep the pride of your county alive. He was your star baseball player was he not? Your good American boy? Your Jericho Jim?” The town cheered assent. “Then you, you good people, must do what is right. We, your protectors, have provided your native son with Extenze, but this miracle drug, the God chemical, is not cheap and we, your humble servants cannot be expected to provide him with life, animation itself, without asking for something in return, could we?” The townspeople looked around concerned, but assented, agreeing that yes, it would be strange to receive life for nothing. The scientist peered heavenward and continued, “Within these mountains, the mountains that have so protected and nestled you, lies a metal that we scientists, officials, and soldiers prize above all else, and need to survive. It sustains us you see, gives us purpose. Retrieve for us this metal and we shall allow your golden son to live forever! Delve within the mountains, into the deep dark for what glitters in the sun and you shall have your boy for eternity!”

Large trucks carrying equipment (drills, picks, shovels) could be heard rumbling down Main street. Soldiers began forming lines out of the townsfolk and directing them into camps, already established, at the mountains’ respective bases. “We will keep the boy safe, under our care and supervision until such time as you good, honest people can uncover that which the mountains protect from our grasp.” Silently, the townspeople acquiesced, corroding the organic features which had once provided them so much security.

The dead boy, who was now referred to simply as Jericho, was taken to a secret location for safe-keeping. He became a symbol for the workers. His melted likeness, posted on every wall, brought them pride and purpose. It resided atop the thresholds leading into the mines and they would touch it longingly as they descended into labor. They fell into the routine of camp, quickly forgetting their former lives, thinking only of Jericho living on chemically in some government warehouse, for them.

. . .

Jericho awoke in a building, starkly white and brightly lit, wearing a white jump-suit. His room, adorned with a white cot, a porcelain toilet, and a mirror, had one door with a little sliding panel, roughly at head level, for observation. He could see, but not like before. Instead of having five separate senses, it felt to him as if he had one all-encompassing sense, allowing him to feel the physical proximity, shape, heat-signature, and texture of things by sheer force of will. If he exercised this feeling, new to him in every way, he found that he could determine the location of people within the facility that, had he had eyes, would remain invisible. Smells, colors, and sounds no longer meant anything to him: people’s words seemed to be injected directly into his brain while his words, audible, had no place of origin but seemed instead to be projected equally throughout a given space. Pain, no longer necessary in a body unhindered by malfunction, slowly lost meaning to Jericho as well. The lightening bolt had melted his features completely, lending his head a pure, pill-like aspect. If it were not for his clothing, it would be difficult to determine which side of his body was the front. And because his senses were no longer beholden to a forward direction, he dismissed the customary desire to face whatever he sensed. He felt spherical, total, undefined. The only way he registered time’s passage was by noting the intervals between doses of Extenze. He no longer required food or drink, but sometimes he found himself aching, in a desolate, dull, and almost imperceptible way, for the pill his head so resembled.

One day when he awoke the door was open. It had been a week since he last took Extenze (the period between doses had decreased while the dosages had increased) and he was feeling rather desperate. The longer he went without the drug the less acute his sense became, as if he were slowly fading out of existence. He walked, his gait lurching and uncoordinated yet somehow precise and strong, through the open door and into a giant and expansive hangar. A length of bullet proof (presumably) glass, head level, extended down the entire building and rows of observing heads were visible through it, staring expectantly. Over a PA system, the hairless scientist brightly announced that if Jericho desired his next dose of Extenze, he would have to complete a series of tests. “We, who have so generously prohibited you from dying now waste our time and resources on you without recompense. What are we to think? Have we not given you life itself? Have we not provided for you and loved you like a son? Are you not grateful?” Jericho projected to the scientists that indeed he was grateful to be alive, despite his being imprisoned and would, if he could, give them what they wanted if they would only allow him to reach out to his family, his town. Having interpreted this, a disappointed and hairless facade appeared on a massive display to Jericho’s left. He did not turn towards it, but sensed it nonetheless. The head shook, “I feared you might exhibit insolence in your newfound animation. This is much bigger than you, your small, petty life. This is for science! For government! For war! Do everything we ask and we shall return you to your family... once we have what we want.”

If he were still alive in the old way, Jericho would have experienced fear. But now it was something different. “What is it you would have of me?”

The gigantic hairless head smiled. “Entertainment,” he said gleefully as cameras, from multiple and artistic vantage points, were produced from the hangar’s white walls.

. . .

The town resembled ancient ruins. There being no place to deposit the tons and tons of earth the laborers were removing from the steadily hollowing mountains, they had simply begun dumping it over the town, burying it. The old houses and businesses poked filthily from the dirt, as did the faces of the those who used to reside in them. Vestiges. All of the animals, dogs, horses, cows, died of neglect and the crops were left untilled--the folk now subsisted on rationed protein and vitamin blocks only.

The old relationships, familial, professional, friendly, had disintegrated into the single purpose of recovering Jericho. The hairless scientist appeared at the camps occasionally to encourage the laborers, showing them photos and videos of Jericho, their savior. Almost no glittering material had been found within the mountains and the hairless scientist blamed their motivation. “Do you want to see your golden boy again, my good townspeople? Do you want him to stay safe and to represent you proudly? Do you even care? Look what I have been forced to do, look how I have been forced (by you people!) to treat your savior in order to properly motivate you slovenly cretins.” He stepped to the side revealing a screen and pressed a button dramatically, starting a show.

In each successive video the scientist had placed Extenze farther and farther away from Jericho, introducing obstacles and puzzles, forcing him to make sacrifices both moral and physical to reach it. No matter the shape or constitution of Jericho’s body, Extenze kept him animate and purposeful, so the scientists, desiring to know the full extent of his abilities, forced him to endure tests no living man could. The workers looked on horrified as their savior hung himself and cut off all of the fingers on left hand. Broke the necks of twenty consecutive golden retriever puppies. Publicly endorsed slavery. “Is this what you want, people?” asked the scientist rhetorically, “Just give me the metal and he will be returned to you, your boy, whom I saved out of the goodness of my heart and whom I protect for your very sakes. Tell me, how am I to convince you, ye unbelievers, to find the mountain’s prize?”

Skinny and defeated the former townsfolk resumed their work with a fervor that seemed impossible due to their frailty. Descending deeper and deeper into the unforgiving earth.

. . .

“What if I refuse to entertain you?” replied Jericho in his almost telepathic fashion, “Preferring to die, truly, than to be controlled.” The panel of heads visible through the glass strip laughed and the hairless projected head cocked, raising its left eyebrow, leering. “I assumed, given your brush with the abyss that you might consider that route. However we have taken precautions to ensure that you stay leashed, firmly. Replacing the hairless scientist on the screen were images of his former townsfolk, skinny and ragged, streaming in and out of the mountains. Images of himself were posted everywhere around them and the workers seemed enamored with them. Stopping to touch or even to pray to them, waiting and hoping for his deliverance.

“Only you can save them from this fate,” declared the scientist, “only you can save them from endless toil. Nothing glitters within the mountains, they are working towards a false end, making hollow what was once full, and they will continue to do so until we get what we want from you, Jericho.”

If Jericho still had a face it would look appalled. “What is it that you want from me? This cannot simply be for entertainment’s sake.”

The scientist smiled. “Well, perhaps that is only an unintended consequence. Do you not see the utility in your predicament? You cannot die! Despite what happens to your body, life will cling to you like a disease, and we want to know what an immortal being can accomplish. Give this chemical to a man with the right training, the right goals, and he could finish wars single-handedly, assassinate presidents, bring countries to their knees. We are going to turn life into a weapon!”

. . .

Each time Jericho passed one of their little tests less of his body remained, but alternatively the more Extenze he consumed the stronger his ability to sense became. The circumference of his awareness broadened with each intake and he discovered the ability to sense life (its location, capacity, and status) in whatever form it took. He could feel hearts beating, cells dividing, the sun’s energy absorbing into broad leaves. He hid this particular aspect of the drug from them, deciding to speak only when spoken to, to do their every bidding silently, biding.

Soon, after wrestling a bear to the ground and allowing himself to be bitten by a crocodile, he lost both of his arms. He found armlessness to be freeing. He no longer needed limbs to move physical objects within the world. He could, with concentration, even move himself around without using his legs, not quite flying but just appearing in the location of his choice. His captors (rightly so) began to fear his silent power and began lowering his doses slowly, pitting him against more and more dangerous foes.

One day, when the door to his room opened, Jericho sensed a tactical team of fifty men, trained mercenaries ordered to destroy him, waiting patiently beyond his room’s threshold. Without moving, lying still on his cot, he felt the blood flowing through their veins steadily and rhythmically, intent upon his annihilation. He could feel their thoughts as well, their fears and their hopes and their hatreds. He could see their whole lives, their childhoods and past innocences. With sadness he tried something: he felt out each of their hearts and clenched, killing them instantly.

At this the panel of scientists cheered (he could feel their jubilation) and having achieved their goal, decided that it was time for Jericho to die, really this time. They thought that if they stopped giving him the drug and obliterated his body completely, he would simply cease to exist. Having planned for this scenario, the scientists descended into their underground bunker and lit the hangar ablaze, hoping to eradicate the problem that would soon, in his eradication, make them unconquerably rich and powerful.

Jericho felt the fire start in ten separate locations around the hangar, the reservoirs of gasoline in its ceiling igniting and causing liquid fire to fall from the sky. He had no idea what would happen to him if his body were fully destroyed, burned to ashes, and refused to let himself die after so much pointless performance. He had developed an affinity for the drug and, although he did not fully trust it, he believed in its power. Along with life and space, he could feel Extenze, locate it and connect with it. Sometimes he even felt he could speak with it and it would relax him, telling him that everything would be okay. In the moments before the fire consumed him completely, he exerted his full concentration and brought himself in communion with the scientists’ entire reserve of the chemical. Consuming all of it as the fire consumed him.

. . .

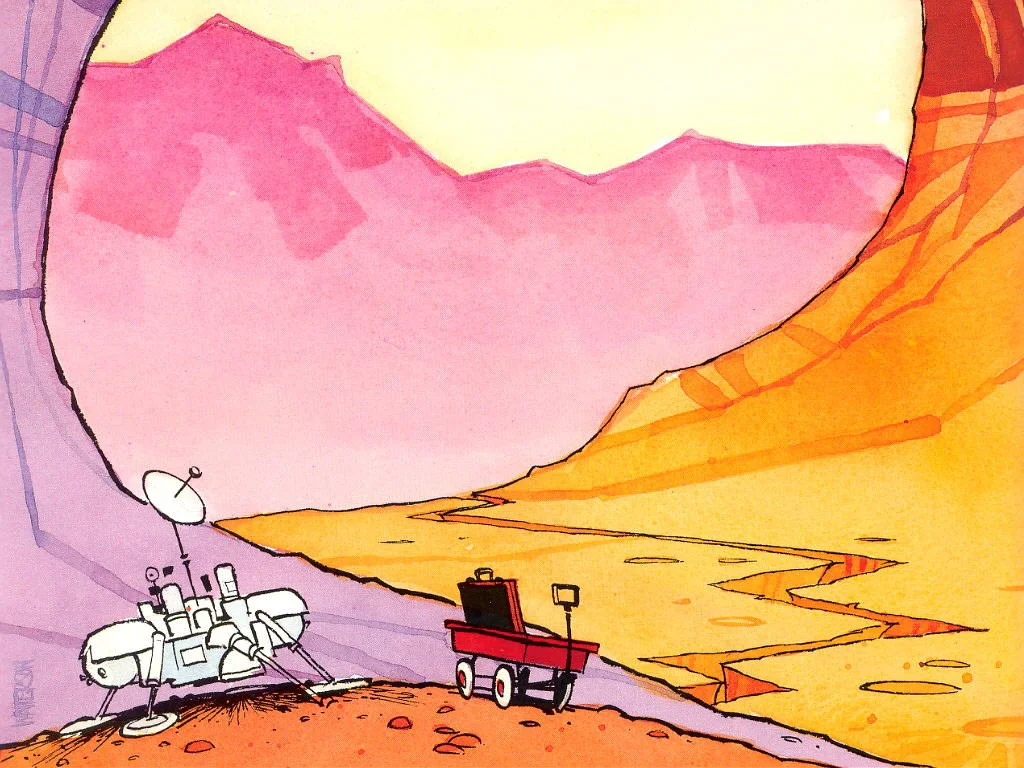

The scientists emerged from the earth smiling at the ashes they had created. Opening champagne bottles and toasting to wealth and war. The town, now completely buried by the mountain’s innards, was irrevocably damaged. The only evidence of its existence being the malnourished skeletons skittering in and out of the mountains. Lazily, the scientists left them to their doom, assuming that they would work until they turned to dust, thus tying off their own loose ends. They languished in victory, caring not a whim for their cruelty and firmly believing in physical existence.

Before the fire had fully consumed Jericho, he had fused himself with the drug, taking well over one-hundred times his previous highest dose. The drug, used to him, accepted his chemical composition and enjoined with it, caressing him, the fire burning away the superfluous flesh and letting him drift into the sky. From his lofty perch he could see both the scientists and the townsfolk and, although he could not see the town itself (for it was buried) he could sense it, feel the structures in the dirt. In fact, he found he could feel everything. Everything that ever was or is, all the beating hearts, dividing cells (even the inanimate bodies) that made up the universe. His awareness stretched astronomically, combining with the chemical structure of the universe, with physicality itself. He knew. And stretched around and through and in things, seeing time laying out before him. Now he observed and studied the world. Evaluating it, and finding it lacking.